Hauraki Rail Trail: Sections C-D ~ Nov 15-18, #6

We left Dickeys Flat under the threat of rain, retracing the trail back through the gorge, to the main route heading South to Te Aroha on a gravel track used to move herds and flocks between paddocks with gates at every farm road crossing.

Our plan as we left Auckland was to keep riding South and leave most of the North to explore closer to the end of our visa. In three weeks, we had covered just under 400 kilometers with over 600 remaining to reach Wellington where we would catch the ferry across Cook Strait to the South Island.

However, we had an added complication that was slowing our pace. The night before leaving Australia, Nivaun’s camera made other plans. It was unclear whether it was a software bug or a mechanical failure but his camera was indefinitely out of commission. After frantic calls to repair shops, the camera was traveling to Sydney for repair with an estimated return via Auckland in more than a few weeks time. Needless to say, each day its absence was ever present on his mind, waiting for the final word when it would ship to Auckland, and subsequently where we might be, so it could then be shipped to us.

Te Aroha

We arrived in Te Aroha in time to resupply before heading to the caravan park outside of town, when to our surprise, we met up for a third time with the local cyclist we had said farewell to on the trail near the falls. He was also staying at the caravan park before getting a ride back home in anticipation of his next bike tour in India.

Before coming to New Zealand, I had heard, that here, even more than in other countries, children are encouraged to travel as soon as they are young adults. But the number of people we were meeting from all over the globe, especially young people on work visas, made it clear how important a broader world view is to understanding our place on this planet and how to peacefully coexist with each other and the earth. To be defined solely by one’s own country, is patriotism in a vacuum, that in the end serves no one.

In another day’s time, our friend had departed and the clouds hung lighter in the sky, cleared of rain. The kids staying at the park had energy to burn, as they swung on the rope under the branch of the old oak tree, pounced on the trampoline and flung themselves through the obstacle course. But one little guy saw an easy challenge and a record to be set, inviting Nivaun to a bike race before we left. Amazingly, the best out of three laps - the young one now holds the record, winning 2 out of 3 in the first ever race against a fully loaded fat bike.

Matamata

The trail leaving Te Aroha was finally free of paddock crossings and followed the edge of the road all the way to Matamata. It was an uneventful ride until we reached a bridge covered in a cloud of bees. We couldn’t imagine why they were there and wondered if a hive had fallen off a truck crossing over the bridge, but we dared not stop in their midst to look below. Surprisingly, they scarcely noticed us dividing the space between them, as we tried to calmly pedal to the other side.

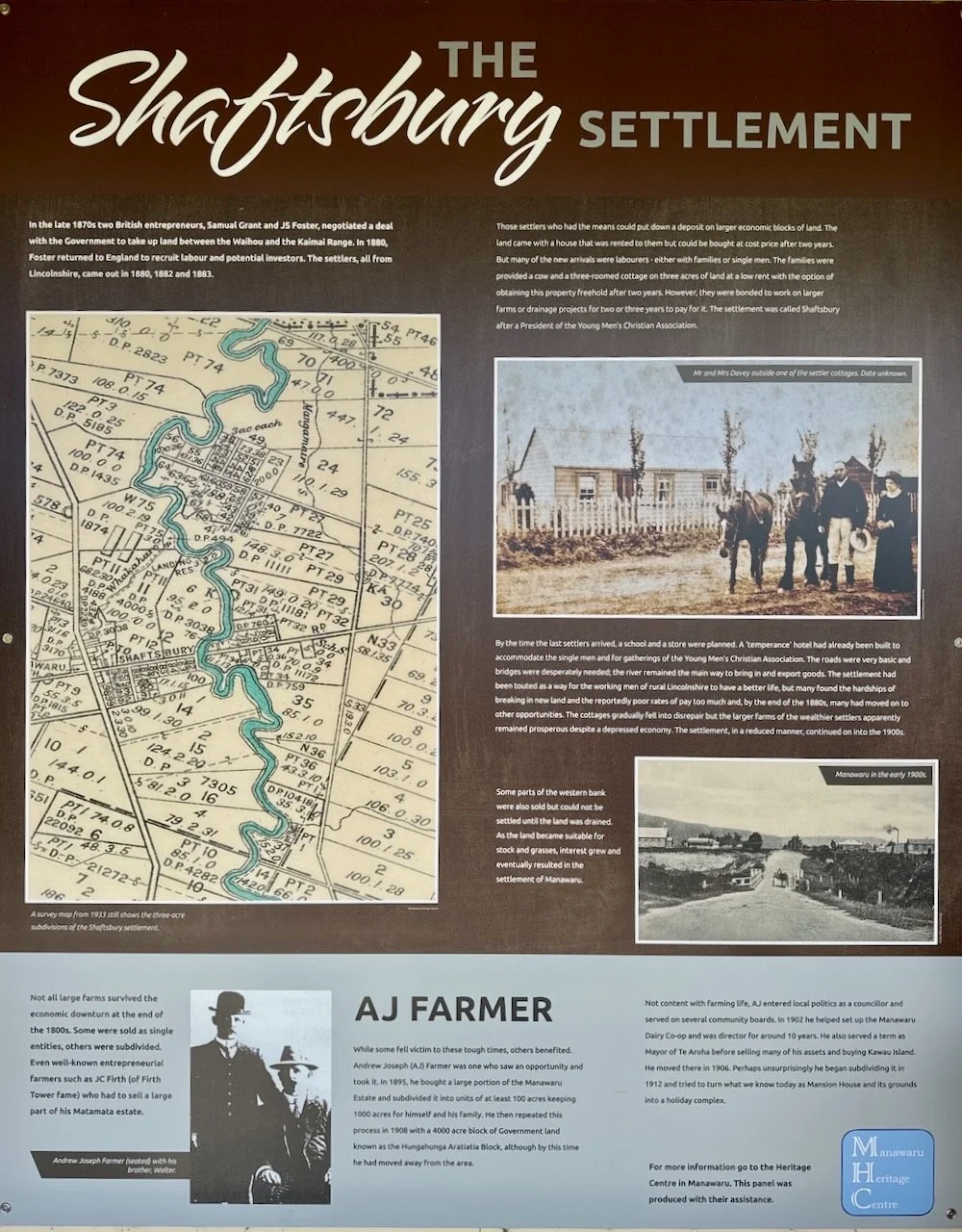

Further along the trail, we stopped to look over the newly installed historical sign boards at the rest stop telling of Maori tribal conflicts, the early settlers looking to profit from the land and the exploitation of the Tuna/Eel. It was clear from just crossing this valley with an increasing number of farms “For Sale”, the era of local farming was quickly giving way to leisure farms, an escape from the city. And it occurred to me, bypassing an opportunity to return the land to those that first cared for it, considering the unresolved dual treaties and the current uprising over the Maori’s representation in government. Even more so these days, I wonder, what would life be like, if lands were returned to their original owners - would the ideals of caring for the land and its wildlife restore some kind of balance? or in this day and age would the human desires for profit and power simply change hands?

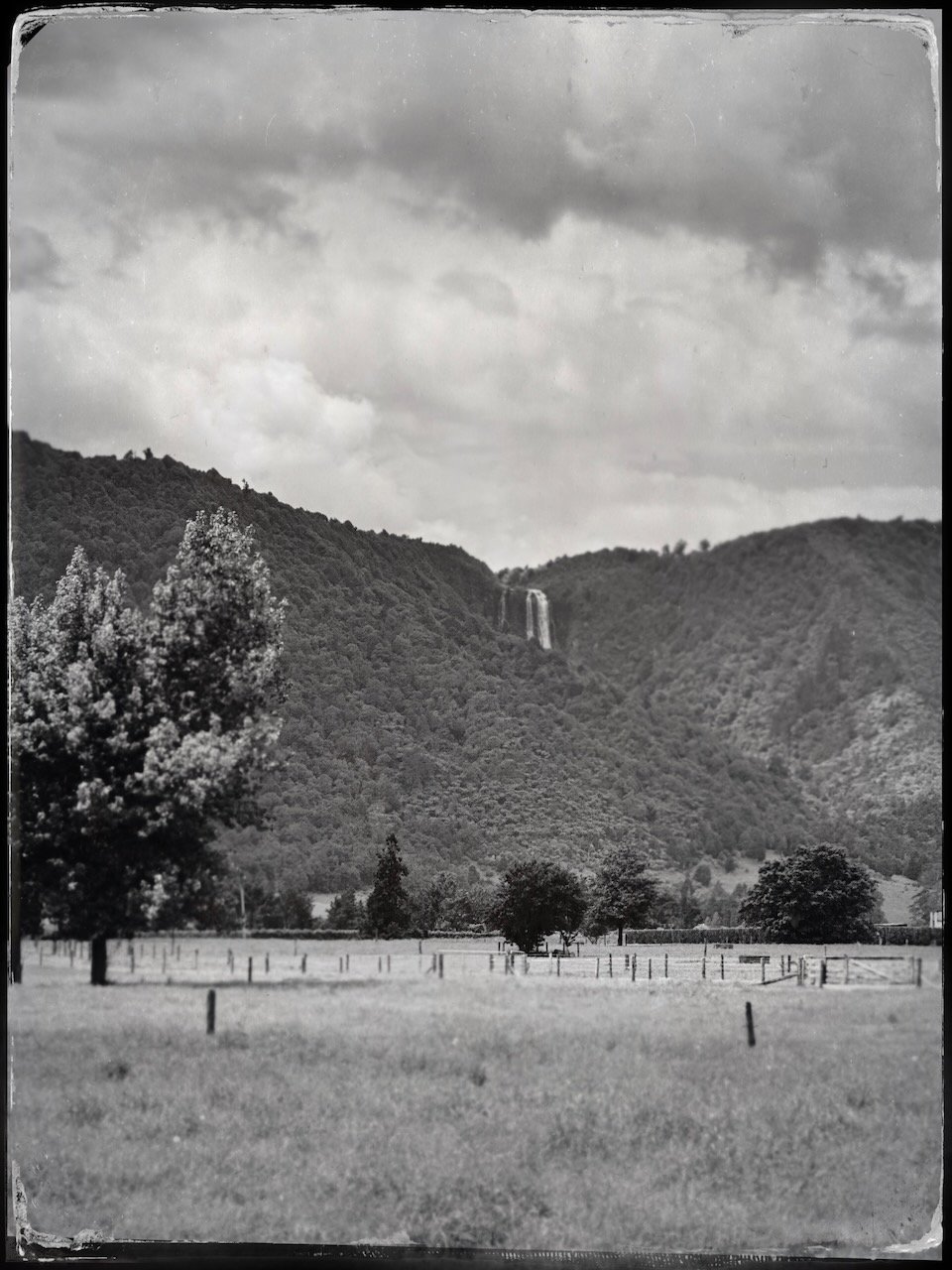

As we got closer to the caravan park just outside of Matamata, across the farmland, tucked into a ravine, a waterfall of PNW proportions came into view and our excitement grew. On the map, it looked as though it was a short ride from the caravan park, giving us a reason to book a couple nights stay for a day hike.

A pattern was clearly emerging, we were not traveling alone, just as we turned the corner to find our designated camp spot in the row of grass, a familiar face appeared - one of the hikers we had met at Dickeys Flat. After finishing the Kaimai Ranges, he and his trail partner had parted ways on the ridge and he was now continuing on to finish the Te Araroa.

Wairere Falls

The next morning, we turned to follow the back road up to the base of the waterfall not knowing what to expect after barely dipping our toes in the magic of the forest at Dickeys Flat. Here we would be climbing 380 meters/1250’ in 2.5 kilometers to peer over the top of the North Island’s tallest water fall at 153 meters. But even more impressive, was the total immersion of ourselves in a thick, lush forest, protected and sacred, for a round trip of 5 kms as the light changed and the shadows shifted. We took our turns hiking the trail and barely had enough time to make it back to camp before dusk. Our souls now overflowing with gratitude that such places exist and that we were here to embrace it wholeheartedly.